Time was, writers submitted their initial draft to a publishing house or a magazine, where editors read and welcomed it. Enticed by a project, an editor may have asked that a few things in the manuscript be explained better, or arranged differently, or fleshed out more colorfully, but when an editor saw promise in a work in progress, he or she took it on. In fact, working with writers was one of the rewards of being an in-house editor. What joy to find a diamond in the rough and help bring out its potential!

Unfortunately, publishers are under such pressure these days that the one thing they want to avoid is writers whose work needs work. What is now expected of authors who submit their writing for publication is more than just promise: it's polish and a finished product.

On the one hand, this is an enormous change for writers, who have to bear the full brunt of submitting a near-perfect manuscript. On the other hand, it's no change at all-just a shift in personnel. Instead of expecting the editorial services of an in-house editor, writers must look first for an out-of-house editor prior to getting a deal. Some literary agents can fulfill this role, but literary agents also are besieged and overburdened, and the cry from their quarters echoes the words of acquisition editors at publishing houses: show me a final draft!

So the ball is clearly in the writer's court to submit a manuscript that doesn't need any more editorial attention. Its structural problems are solved, its language is clear and eloquent, its loose ends are tied up. In other words, it is acquirable and publishable as is. The fact that it got that way with a privately hired (and privately paid) editor is just another facet of the changing literary landscape.

Working with an editor is not a mysterious process, but many writers are not completely clear about what's involved and how best to make use of editorial help. Here are some thoughts gleaned from years' worth of effort as both a writer and an editor.

Above all else, editors are experienced readers. They've honed their instincts and recognize good writing-or the germ of an idea-when they see it, because they've read a lot and thought a lot about the written word. Their primary job is to read closely and question what they don't understand, make suggestions, keep a project on track, move the story and the process forward. Their overarching goal is to bring out the best in their client's writing. This means that a good editor has an open mind as well as fresh ears and eyes and is receptive to myriad voices, forms, and approaches.

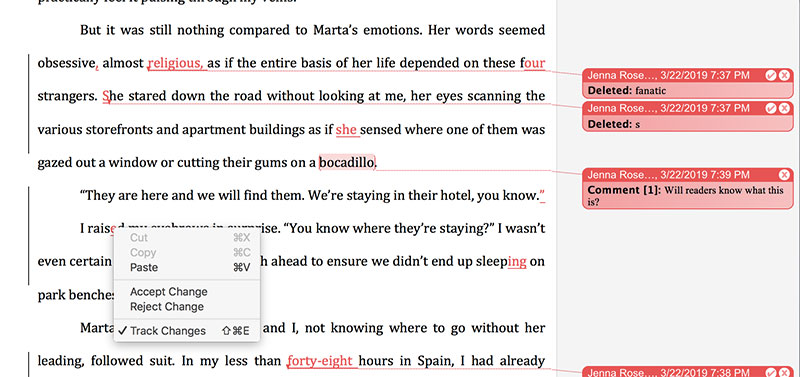

This holds true whether you work with a "substantive editor" (also called a "developmental" or "conceptual" editor) or a "line editor." A substantive editor can help clarify the direction and structure of a piece of writing. A line editor will groom a manuscript and smooth out the edges, correcting grammar and punctuation and refining each sentence once it's mostly finished. Many writers need both, and many editors can provide both levels of editing.

In the case of writing for a particular publication or targeting a particular audience, an editor can help shape a piece of prose to the needs of that publication or audience. He or she serves as a stand-in for the eventual readers. If what an editor reads is confusing, underdeveloped, or naïve-if it evidences faulty logic or repetitive ideas or tired-out language or any number of other common pitfalls-he or she will question those passages, suggest a rewrite, and likely make recommendations as to what to do (say less here, expand that idea there, add more description, be more specific, pull back and give the big picture).

Editors don't necessarily have to know very much about the subject they're editing. Their writers are the experts. In fact, not knowing a lot about a subject is usually a big advantage for an editor. It means that lapses in explanation are more glaring, since they can't be filled in with information the editor already has.

It's quite common to feel defensive when an editor starts to question work you've spent months or even years writing. But to take full advantage of an editor's work, it is crucial to stay open. If your editor questions a passage or a point, or makes a suggestion for a revision or a clarification, you should never (scary word, but apt) reject the questioning out of hand. There are many ways of untangling writing knots, but they all start with pinpointing the problem-something that doesn't sound right, ring true, go far enough, confuses.

It's really important to be amenable to probing. You may think the questions being asked by your editor are obvious, and you may not like the suggested fixes, but you have to appreciate why they are being brought up: your writing is lacking something, or faltering, and your editor-your problem-solving collaborator-is trying to help you identify what the problems are and how to solve them. In my experience, the better the writer the more open he or she is to questions from the editor-from major issues to finicky punctuation.

A good editor will save you from embarrassing errors and help you weed out linguistic lapses into clunkiness or excess verbiage. An editor is not an ogre who wants to impose his or her own way of thinking or boss you around but your behind-the-scenes partner who is trying to bring out the best in your work. Novice writers aren't always aware of this. Experienced writers may have to remind themselves of it.

And everyone at any stage of a project should bear in mind the ultimate goal: getting published. Having an editor who has your best interests at heart can improve your chances of achieving that. And more: they can help you be proud of the words you've written.

- Invaluable Lessons I Learned About Editing From “Turn Every Page" - January 3, 2024

- The Benefits — and Fun — of Freewriting - February 20, 2023

- Writerly Reassurance From a Few Who Have Been There - March 24, 2020