Last Updated on April 10, 2023

Each time a fine editor has his or her way with my writing, I rediscover precisely what I am trying to say and often the best way to say it. And each time I work as an editor with a client who attends to and cherishes what I offer, I walk away not only financially compensated but confident that both of us (and the writer's work) are better off.

While I recognize writers' experiences with editors is not always ideal, it is critical to learn how, when, and why to rely on an editor's experience and wisdom. Too often what could and should be a beautiful partnership — and must be if the work is going to sing — turns into a struggle, for both the writer and the editor.

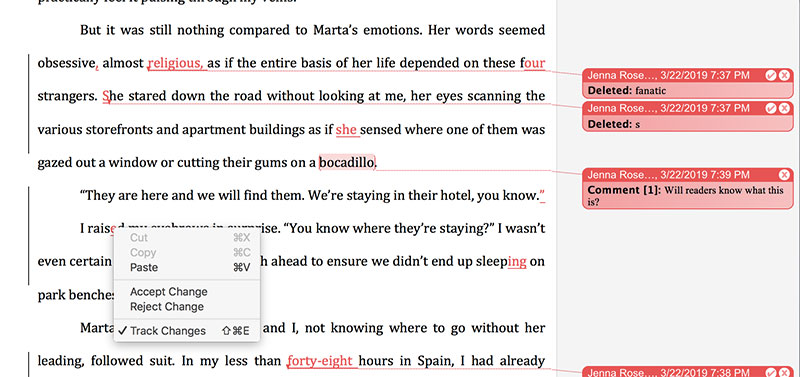

A few weeks ago, an experienced and highly skilled colleague called for commiseration and advice on a client who refused to pay for the edit already done on the opening of his manuscript. In an email exchange, the client had promised to pay for the work but then apparently changed his mind. “I didn't use any of your changes,” the client argued. “Why should I pay?”

We laughed, sourly, but soon after that, I read Nathan Heller's "What Enron Emails Say About Us" in The New Yorker. I was especially struck by his conclusion: “The true wellspring of civilization isn't writing; it is editing.” And not long after that, when renowned editor Judith Jones passed away, the writers whose work she had so eloquently enhanced wrote page after page of praise for what Jones's pen had done for them and their works.

Like the best editors among us, Jones held to the notion that above all an editor must recognize that each author has a unique voice, and that the editor must be a “diplomat…. It's not your book,” she wrote, “but you can subtly try, and it usually ends up that the writers express themselves so much more clearly. At least, that was my experience.”

To test Nathan Heller's hypothesis, Jones's philosophy, and my own experience as both writer and editor, I reached out to a number of colleagues and asked them to answer two questions:

- What do you ask of/expect from an editor (both those hired independently and those in the publishing industry with whom you have worked)?

- And to the editors: What are some of your best and worst experiences with clients?

Twelve people I interviewed expressed similar ideas; I present here a few for your consideration:

William Eaton, editor of Zeteo Journal, described beautifully the push/pull of the editor/writer relationship:

“When I work with editors (whose work I greatly appreciate!), I am at first deeply offended by their responses, questions, and edits. After I've calmed down, I find that one-third are excellent suggestions, one-third are useless, and the other third... notions for wrestling with. But it's precisely the wrestling that's the valuable part. It forces the writer to come to terms with his own piece — what aspects he is willing to fight for and what not and so forth. The tension and conflict between editor and writer are what tighten the piece.”

I am certain that the writer who didn't “use” my friend's edits was forced by looking at his editor's notes, comments, and changes to come to terms in a new way with his own piece. If he had recognized that the tension and conflict between editor and writer helps to tighten the work, he wouldn't have misunderstood — and been so stingy.

To a great extent, the attitude of the writer going into the process makes all the difference. As Amy Wallen, whose newest memoir When We Were Ghouls: A Memoir of Ghost Stories will be published next spring, wrote:

“I go into an editing process always very insecure. I tend to think that my work is unworthy and, because of that, I have had to learn to be careful not to do everything the editor says. I learned the hard way to listen to my gut.”

Wallen emphasized the point Eaton made, adding, “…but more often than not, I have found the editor's insight invaluable. While I may not apply all their suggestions, their edits and points made are often triggers for something bigger that I need to do. They hand me the keys and it's up to me to open the doors.”

Nora Zelevansky, whose most recent novel is Will You Won't You Want Me?, makes a similar point: “My idea of a good editor is someone who improves what I've written. That's basically it. If that person is willing to teach me something along the way, then I've really won. My expectation professionally, though, is just that an editor will improve the clarity of the piece — whether it's a book or an article, not make it worse. I want to be able to feel proud of any piece with my name on it, once it's been edited.”

This isn't to say that all editors are equal. As Zelevansky, who also works as an editor, points out, “I have had a couple experiences with articles where I felt that the story was worse after the fact. That's disappointing.”

Willie Wilkerson, author of the forthcoming memoir Hollywood Godfather, says, “Editors are supposed to catch me when I fall (and I do that quite well, by the way).... Without my editors, I don't exist, it's that simple.”

One of the best editors in the business, Brooke Warner of She Writes Press, has some invaluable advice to offer in her blog, Confessions of a Book Editor, and an eye-opening description of the different kinds of editing you might be seeking. As Warner explains it, while writing is a solitary, sometimes even lonely venture, publishing is a collaborative effort.

There is, as Warner says, “room in publishing for masters and apprentices, as long as both subject themselves to good editing. You cannot write your magnum opus as your first effort. It's something all authors build toward.”

It's important to study carefully the kind of editing and editor you need, and groups like LA Editors and Writers Group provide a useful guide. Ask questions, certainly. Reject some ideas.

But recognize that wise writers keep hearts and minds open and understand that their editors are there to help identify a work's weaknesses and strengths. A writer's mission is to make his or her work the best it can be, and an editor's sole mission is to help and guide and instruct so as to eliminate the weaknesses and enhance the strengths so that the work will sing.

- Tips for Overcoming Common Fears About Writing Memoir - February 21, 2024

- 3 Reasons to Write a Book Proposal for Your Nonfiction Book - March 24, 2023

- Finding a Literary Agent - November 7, 2022