Last Updated on March 23, 2022

The writer William Carlos Williams called a poem “a machine made of words,” and in both writing and editing, I find it useful to think of narrative as a sort of machine as well — a machine made to transport a reader through story.

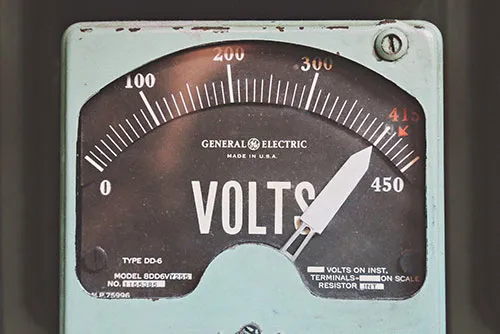

As is true for any other machine, the machine of story requires energy to function — to carry its reader from a beginning, through a middle, and to an end.

Though there are various tactics and techniques that can juice up a narrative, the primary source of energy that propels fiction and memoir is derived from conflict. When narrative tension is flagging, many writers feel compelled to drum up energy by developing the action, but far more often the remedy lies in developing our characters themselves.

So what is conflict? Sometimes conflict is just another word for indecision: Should I stay, or should I go? Sometimes it's another word for desire: I want x, but I don't have it. I want love; I want bravery; I want to be left alone; I want a seat on the subway; a part in a play; a kiss from a certain someone; a donut.

If, for example, your character desperately wants a donut in the middle of the workday, there may be no limit to the number of shortcuts she'll take in finishing a project in order to get to the donut shop before all the chocolate glazed are gone. Merely by dint of asserting this desire-for-donut, you're equipping your narrative with a certain amount of energy; the behavior driven by this desire sets a story in motion through scene.

While such a logistical desire may have enough energy to power a scene, it probably doesn't pack enough punch to drive the entirety of a narrative. In other words, a story's potential energy lies less in the situations a character encounters than in the very constitution of the character herself and what is at stake for her in that situation. Who is this person so desirous of a donut that she's willing to compromise her work? Is pursuit of this donut an act of self-sabotage? Is it a manifestation of some deeply held resentment of her boss or of a lackluster breakfast she had that morning? Perhaps one served up guiltily by a spouse newly discovered to be cheating?

The key to drumming up narrative tension in this story has less to do with throwing more obstacles between protagonist and donut than by bringing greater dimension to the person depicted on the page.

Who, exactly, is the person experiencing this desire? What does this person want in the grand scheme of things?

Unfortunately, these are the kinds of questions that can make us freeze at the keyboard. Even if we're writing about experiences we lived through, it can be difficult to identify and portray the complex nature of our longing at the particular time we're writing about.

In such instances, it can be useful to take a step back and shift focus, to consider this character's Defining Characteristic instead.

"But I contain multitudes!" our characters might protest. "Not in this draft," we must insist...

In life, we all want to be recognized as multi-faceted and complex, but on the page — in story — a character is often content to be reduced to one particular characteristic. At the very least, thinking of a character this way can help the writer figure out what aspects of this person are relevant to this particular piece of writing.

Consider, for example, the Cowardly Lion.

Right there in his single, scaredy-cat, utterly reductive characteristic, there is suddenly Conflict — which means there is suddenly story: He's a coward — but he wishes he weren't.

And in that simple, utterly reductive dilemma, there's an inherent question: Is he stuck being a coward forever?

By keeping just one fundamental and entirely reductive attribute in mind, you can heighten the energy of every scene that follows.

Not only does this characteristic drive the lion's decision to accompany Dorothy to Oz, exploration of this seemingly simple characteristic is enough to drive the Cowardly Lion's entire storyline. What does it mean to be a coward? How does it impact him in his daily life? How does this understanding of himself limit his vision for his own future? Is he even brave enough to travel to Oz?

Is our donut-seeking character always walking around feeling deprived? Is she simply insatiable on all fronts? Or has she historically settled for less than what she wants and finally just wants her goddamn donut?

Reducing her desire to one specific root can concentrate its energy, making it easier to leverage meaning within a given scene and across a narrative as a whole.

Potential Energy + Kinetic Energy

In mechanical physics, there are only two kinds of energy: potential energy, which is stored energy, and kinetic energy, which is energy in motion. Like the coiled spring inside a jack-in-the-box, a single defining characteristic holds potential energy that can be activated and explored throughout the larger course of a narrative. In fiction and memoir alike, a character is trapped in the box of herself, spring-loaded with internal conflict.

And just as the potential energy of a jack-in-the-box requires the force of a turned handle for its spring-loaded release, the characters we present on the page must be subject to forces that engage and activate the energy they carry. In other words, an antagonist must step into our narrative to provide the force that sets our story in motion, transforming inner turmoil into scenes that engage, challenge, and explore it.

Consider this scenario: Dorothy is trapped in the witch's castle and the Cowardly Lion must decide whether or not to try to save her. He really wants to save her — what a good friend she has been! — but does he have the courage to do it?

Imagine him standing tormented at the castle's entrance, steeling himself to run inside, to brave those terrifying flying monkeys and rescue his new friend.

He wants to do it; he can't. He wants to do it; he can't.

Because his defining characteristic is so clearly established, it doesn't even matter what decision the Cowardly Lion makes. If he runs into the castle like a hero; if he cowers and runs back into the woods; if he stands there ruminating until, at long last, he wills himself to play hero but it's just a second too late — any one of these outcomes can deliver a satisfying sense of story expressly because each engages the potential energy of the character's defining characteristic and releases it to set scene in motion.

So if you're finding that your narrative's energy is flagging, you may find it useful to consider the following: If you absolutely have to pick one, what is your protagonist's defining characteristic and how does this characteristic inform the scenes that unfold?

- Fiction, Memoir, and the Machine of Story - September 3, 2019