Last Updated on March 23, 2022

Ever been tempted to tell your story?

Today it's easier than ever to leave a legacy, publish a family history, or create a volume of the story of your life. Independent publishing, print on demand, and software like Adobe InDesign can turn out a beautiful and completely professional looking tome. Naturally, you want that story of yours told as fully, richly, and authentically as possible. Here are some tips and guidelines to help you get started:

FIRST, 4 FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS

For whom are you writing? Your family? Your community? A larger audience who might be interested in the times you lived in and the role you played? This will affect your style, tone, and voice.

Why are you writing a memoir? Do you mainly want to leave a record of your life and family for those who already know you? There's value in even an informal reminiscence for your circle and descendants, and many memoirists discover that such reflections inform their lives with a fresh, occasionally even therapeutic perspective. “Sick of being a prisoner of my childhood,” Clive James explains in Unreliable Memoirs, “I want to put it behind me.”

Writing a memoir can help you find understanding and peace of mind as you work through your life narrative and its challenges and disappointments. At its best, it's a search for the truth and achieving some perspective in your retrospective. Memoirists, asserts writing teacher and author Dinah Lenney, want to testify; they have a single story to tell.

It's not necessary to create what memoir mentor and writer William Zinsser calls a careful act of literary construction, but it's helpful at the start to have an idea of what you want at the end.

Do you really want to write a memoir? A memoir is not a journal or diary. A memoir is not a Christmas letter. A memoir is not a chronicle.

Memoir is not even autobiography, which is the story of an entire life; memoir is just one story from that life, or, as Gore Vidal put it, how one remembers one's own life. It's focused yet flexible.

Is what you're writing likely to be of true interest to someone else? Ever keep a diary when you were a teen? Remember how unbearable the thought was that someone might see it? Yet how potent, really, do you think it would be if someone saw it today? Most early diarists tend to a then-I-did-this, then-I-did-that account of the mundane and quotidian. The goal in memoir is to take one step back from the ordinary and give it enough perspective to include and engage the reader. Instead of, say, “I'd take a walk and come home and have a sandwich,” show us why you took that route, tell us what would usually hit you first when you walked through the door, describe what was in that sandwich (and even who made it for you). The details immerse the reader further into your story, details you might not include if writing for just yourself.

Memoir may not arc over an entire life, but it still tells a story. Or, to paraphrase Alfred Hitchcock, it's life with the boring bits cut out. Ideally, you want a clear start, a gathering conflict, a resolution, and a fundamental change in you, the narrator, as a result (this last part is important). Can you identify these elements in a theme? Consider the ones suggested below, and if any one of them ignites you, you've got the makings of an engaging and compelling memoir.

CHOOSING YOUR STORY

Can't figure out how to begin? Break it down, and consider possible themes. Then pick one, or even part of one.

- Time period (growing up, college years, young adult in the big city, marriage and family, and so on)

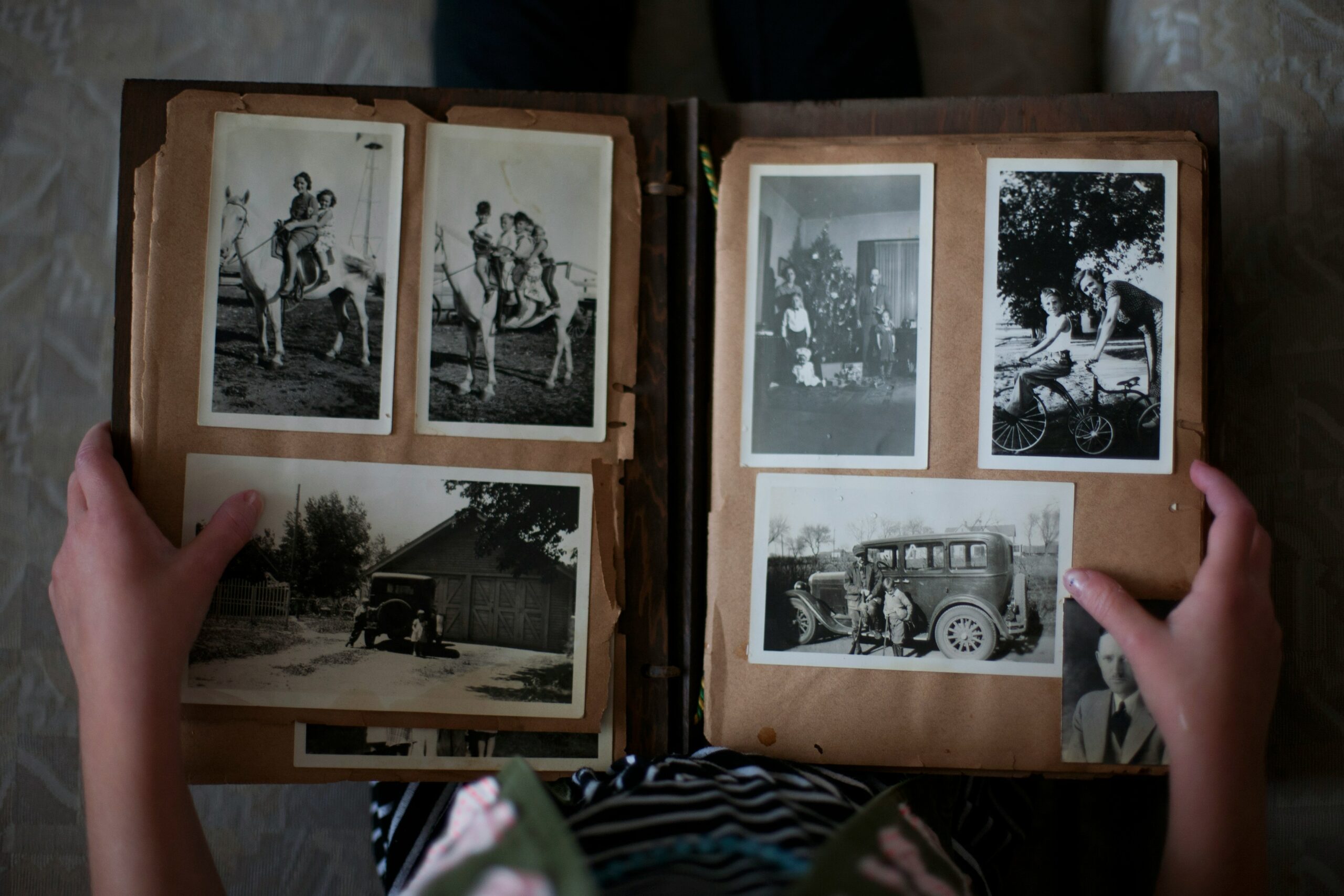

- Key connections (friends, your parents/family, a marriage, people who influenced you; one side of the family or another)

- Physical places (your homes, retreats, communities)

- Historic/political (war experiences, activism)

- Personal hardship, recovery (illness, addiction, loss, bad choices)

- Personal achievement/development (health, business success, travel, cooking/remodeling/crafting; important choices – conflicts, passions, lessons learned)

Or … start priming the pump with brief stories, anecdotes, incidents, and accounts, especially those you can situate in a particular time and place. Be generous with your details. Work on each piece separately, each of those miniatures, those glimpses, stories, and reflections that come to you and resonate.

Don't worry about noting the “important” occurrences. Large events are best brought to life in smaller sketches and stories. The more detailed and personal the episodes, however minor, the more effective and, ironically, universal they become. Think small, William Zinsser reminds us.

Don't …

- Comment too much on yourself or what you've written; if you're a youngster glued to the radio listening to the news or getting your rock ‘n' roll fix, no need to remind us there was no TV or internet then.

- Get so personal and self-absorbed that what you write is more diary than memoir, more laundry list than reflection.

- Edit yourself or worry about privacy – yours or your family's or circle of friends. There's time for that later. Much later. Be brave; writing a good memoir that digs deep and holds truth takes courage.

- Worry about chronology. Start with the strongest images or events; think of it as a tease and trigger to help launch your story.

- Be vindictive or self-pitying, whine or play victim. Not pretty, not engaging.

Always …

- Keep your audience in mind. Try writing for one ideal reader.

- Include specifics and details for color and to make your story come alive.

- Try if you can to tune in to a place of understanding, forgiveness, love; it will make even the most formidable events, heartbreaks, and challenges more honest, vibrant, and universal.

- Write, write, write. It takes practice, just like anything else – playing the piano, chopping an onion, speaking a new language, navigating an argument with your spouse. Lash yourself to the mast and just do it. No one has to see it. Not yet. Need a spur? Start by writing (really writing) to a friend. Make the next email something you've thought about, something you're proud of.

And finally …

If you're still stuck and your story clamors to be told, find a class or a writing teacher, editor, or ghostwriter to coach you. Many of us don't have the time or patience to tease out our tale. That's OK too, because professionals abound who are experienced and savvy about helping with this, and who can save you time and considerable misery.

But if this is something you want to do, and if you do not want your story – or that of a family member -- to die with you or them, then get started. Soon. Before, as Zinsser warns, time surprises us and runs out.

Resources to Help You Get Started

So You Want to Write a Memoir: 10 Great Tips

William Zinsser on How to Write a Memoir

American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA) Newsletters

Online Classes, Webinars, Help

National Association of Memoir Writers

- Why You Need an Interior Designer for Your Self-Published Book - June 7, 2022

- 6 Reasons Why You Should Write Your Book in Microsoft Word - December 8, 2020

- Tricks of the Editing Trade: Word, Track Changes, and the Master Document - May 16, 2019