Last Updated on March 23, 2022

When I want to escape the uncertainty and stresses of life, I seek refuge in fiction. I scour the shelves of my local bookstore, or — if precarious times prevent me from leaving the house — peruse books online in search of that unique story that will captivate and maybe even change me. Whether I'm in a brick and mortar or somewhere in cyberspace, I will while away hours sampling the first page or two of the opening chapter, hoping to be lured into a new world. When that happens, I'm nothing less than thrilled — and I buy the book.

When I want to escape the uncertainty and stresses of life, I seek refuge in fiction. I scour the shelves of my local bookstore, or — if precarious times prevent me from leaving the house — peruse books online in search of that unique story that will captivate and maybe even change me. Whether I'm in a brick and mortar or somewhere in cyberspace, I will while away hours sampling the first page or two of the opening chapter, hoping to be lured into a new world. When that happens, I'm nothing less than thrilled — and I buy the book.

That's how important the beginning of a story is. It can make the difference in gaining the attention of a prospective agent, acquisitions editor, and ultimately the reader.

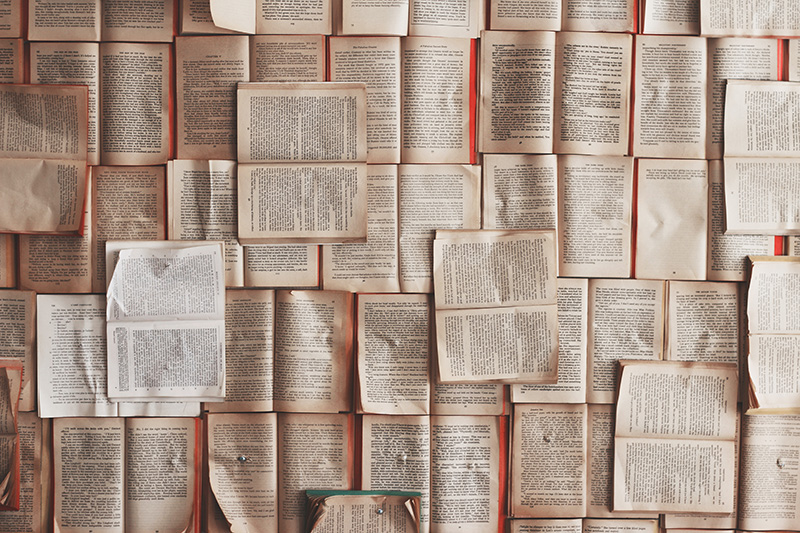

At the opening of a book, the writer makes a promise to the reader: “Trust me. I have a tale worth telling.” It is the start of what John Gardner refers to as “the vivid and continuous fictional dream” that engages the reader, keeps her turning pages. Something on page 1 has stimulated her brain, fired those neurons, and hooked her in.

The Promise of Page 1

“Page 1,” John Gardner tells us in his book The Art of Fiction, “even if it's a page of description, raises questions, suspicions and expectations; the mind casts forward to later pages, wondering what will come about and how.” Readers may not know what lies ahead, but the opening has intrigued them enough to keep them reading to find out what happens next.

I tell new writers that readers won't wait until page 50 for the good stuff. Not many of today's readers have been endowed with that kind of fortitude, and literary agents — who have an infinite number of manuscripts to read and a finite number of hours in the day to do it — have been known to stop reading if nothing on those first few pages keeps them engrossed. You have to entice readers from the start. It's part of that promise, that contract made with readers: that if they keep reading, they won't regret it.

“The first page is a gateway,” Margaret Atwood says. “It's a door into the book…. So, what you want on the first page is something that is going to beckon the reader in.”

So, how do you find your way into the book? How do you start? It's not easy. John Irving refers to it as “plodding work.” He wouldn't begin a book until he knew as much as he could “stand to know before putting anything down on paper.” For The Cider House Rules, he said he had to “gather so much information, take so many notes, see, witness, observe, study — whatever — that when I finally was able to begin writing, I knew everything that was going to happen, in advance…. I want to know how a book feels after the main events are over. The authority of the storyteller's voice — of mine, anyway — comes from knowing how it all comes out before you begin.”

In Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration, and the Artistic Process, Stephen King says that when he starts a book, he composes in bed before going to sleep, trying to write the opening paragraph. “Over a period of weeks and months and even years, I'll word and reword it until I'm happy with what I've got.”

Ideas for Hooking Your Readers From the Beginning

Sometimes discovering the right way to enter the story boils down to what feels right; instinctually sensing what will hook the reader. Then there are times you have to forge ahead and write through the first draft before you find, as you revise, a much stronger opening on page 30. Every story is different, every story has its own doorway. Here are some suggestions to guide you in finding yours:

- Start with an inciting scene. Immerse the reader in the action. Drop your character into a dynamic scene with a hint of the protagonist's conflict. That's where you'll find some interesting trouble.

- Begin at a moment that the character is living at high stakes. Something has happened prior to where the book begins that unsettled your protagonist and threw their worldview out of alignment. Before you write the first sentence, find out what that is.

- Open with a foreshadowing scene to set up the narrative tension and hint at what's to come.

- Create a condition with an element of mystery in it. Charles Baxter does that every time he starts a story. He sets up a question that he and his readers want answered. “Better to start with a small mystery,” he advises, “and build up to a bigger one. The truth about a situation is always big enough to sustain someone's attention.”

- Avoid pages of description before the story begins; don't tread water with long narration before the action starts. Make every word count.

Remember, engage your reader.

Examples of Great Openings of Novels

For inspiration, here are some compelling openings of novels:

They found a body in the Salford Cemetery, but aboveground and alive. An ice storm the day before had beheaded the daffodils, and the cemetery was draped in frost: midspring, Massachusetts, the turn of the century before last. The body lay faceup near the obelisk that marked several generations of Pickergills.

— Bowlaway, Elizabeth McCracken

I might have been ten, eleven years old — I cannot say for certain — when my master died.

No one grieved him; in the fields we hung our heads, keening, grieving for ourselves and the estate sale that must follow. He died very old. I saw him only at a distance: stooped, thin, asleep in a shaded chair on the lawn, a blanket at his lap. I think now he was like a specimen preserved in a bottle. He had outlived a mad king, outlived the slave trade itself, had seen the fall of the French Empire and the rise of the British and the dawn of the industrial age, and his usefulness, surely, had passed. On that last evening I remember crouching on my bare heels in the stony dirt of Faith Plantation and pressing a palm flat against Big Kit's calf, feeling the heat of her skin baking up out of it, the strength and power of her, while the red sunlight settled in the cane all around us. Together, silent, we watched as the overseers shouldered the coffin down from the Great House. They slid it rasping into the straw of the wagon and, dropping the rail into place with a bang, rode rattling away.

That was how it began: me and Big Kit, watching the dead go free.

—Washington Black, Esi Edugyan

Let me begin again.

Dear Ma,

I am writing to reach you—even if each word I put down is one word further from where you are. I am writing to go back to the time, at the rest stop in Virginia, when you stared, horror-struck, at the taxidermy buck hung over the soda machine by the restrooms, its antlers shadowing your face. In the car you kept shaking your head. “I don't understand why they would do that. Can't they see it's a corpse? A corpse should go away, not get stuck forever like that.”

— On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong

She lived in the graveyard like a tree. At dawn she saw the crows off and welcomed the bats home. At dusk she did the opposite. Between shifts she conferred with the ghost of vultures that loomed in high branches. She felt the gentle grip of their talons like an ache in an amputated limb. She gathered they weren't altogether unhappy at having excused themselves and exited from the story.

— The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Arundhati Roy

I would like to write down what happened in my grandmother's house the summer I was eight or nine, but I am not sure if it really did happen. I need to bear witness to an uncertain event. I feel it roaring inside me — this thing that may not have taken place. I don't even know what name to put on it. I think you might call it a crime of the flesh, but the flesh is long fallen away and I am not sure what hurt may linger in the bones.

— The Gathering, Anne Enright

- Should I Fictionalize My Memoir? - June 21, 2024

- Do I Need a Writing Coach? - July 13, 2023

- How to Improve and Inspire Your Writing: 7 Books That Will Pave the Way - April 25, 2022