Last Updated on February 15, 2022

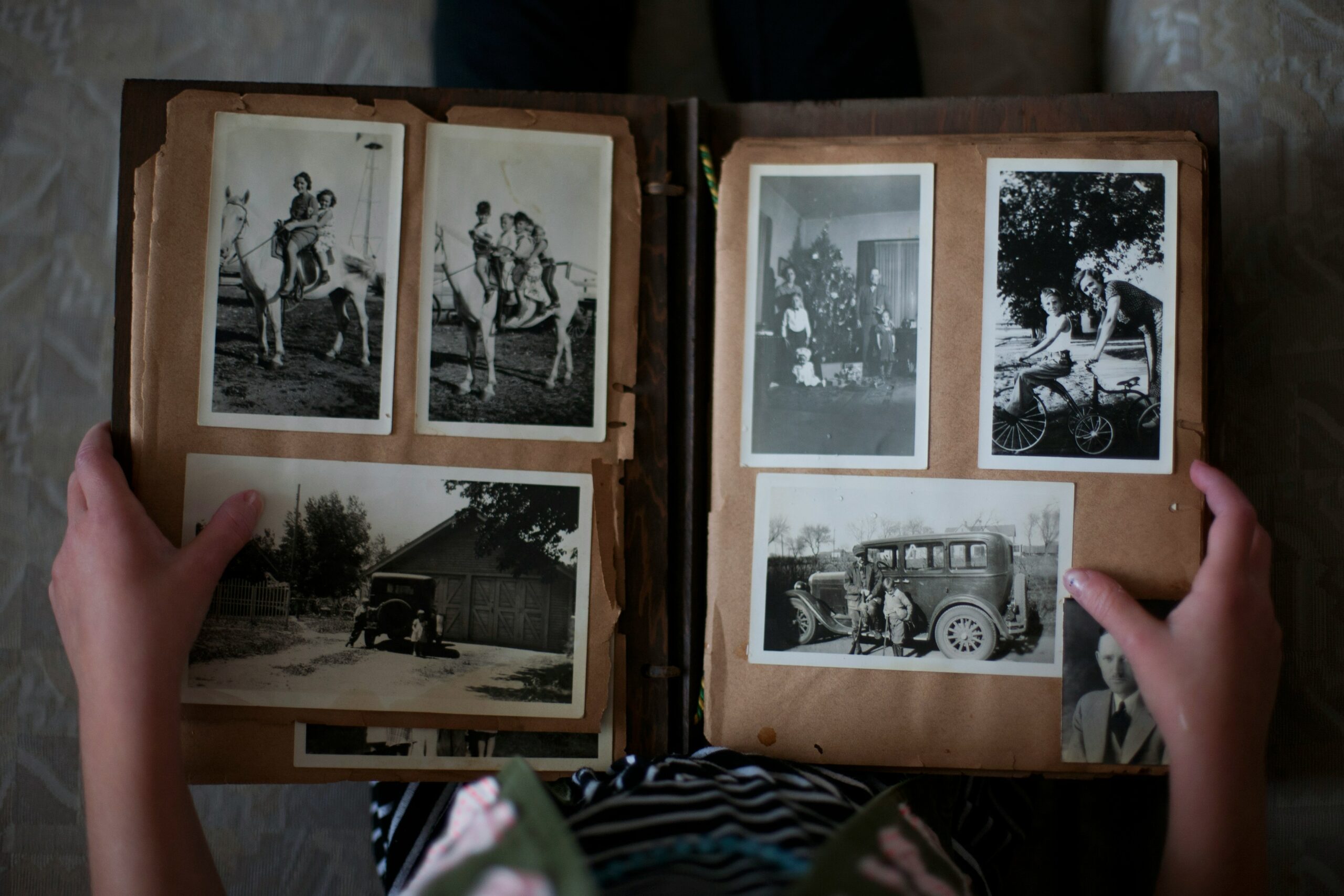

We all remember where we were when something eventful happened in our lives, whether the incident was personal or not. Thinking of the event's location instantly conjures the way we felt during that time. According to psychologists, “We lock in that memory by linking it to a where... integrating many stimuli together helps us remember something particularly important. They call this process episodic memory formation: the locking of ideas and objects to a single place and time, to forming associations between different stimuli.”

We all remember where we were when something eventful happened in our lives, whether the incident was personal or not. Thinking of the event's location instantly conjures the way we felt during that time. According to psychologists, “We lock in that memory by linking it to a where... integrating many stimuli together helps us remember something particularly important. They call this process episodic memory formation: the locking of ideas and objects to a single place and time, to forming associations between different stimuli.”

Many years ago, when I was studying method acting, I did what was called affective memory exercises as designed by the Russian theater practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski. Later a variant of these exercises called sense memory was used. Its purpose was to help the actor connect with a character. During these exercises, we had to re-examine where an “event” took place by exploring its sensory detail, recreating it through the use of all five senses, examining everything we heard, tasted, touched, smelled, and saw. The specificity of details was essential not only to bringing the event to life but, more important, to generating the emotions that accompanied it. “Feelings,” Eudora Welty said, “are bound up in place.”

If place wields such power, why do we sometimes relegate it to a secondary role when writing story? Welty, in her essay devoted entirely to the element of place in fiction, called it “one of the lesser angels that watched over the racing hand of fiction, perhaps the one that gazes benignly enough from off to one side, while others, like character, plot, symbolic meaning, and so on, are doing a good deal of wing beating about her chair.”

Sometimes clients will submit manuscripts — be it fiction or memoir — in which the setting of their story is vague, generic, populated with nonspecific trees, streams, and houses. I ask what kind of trees, what shape and size the stream, what creature might be emblematic of the house? I remind them that place is an integral element of story and suggest that perhaps they consider place as another character in their own story — with its own past, its own conflicts — a character changing over time.

Place anchors a reader to the story. Think of John Steinbeck's Cannery Row:

Cannery Row in Monterey in California is a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream. Cannery Row is the gathered and scattered, tin and iron and rust and splintered wood, chipped pavement and weedy lots and junk heaps, sardine canneries of corrugated iron, honky tonks, restaurants and whore houses, and little crowded groceries, and laboratories and flophouses. Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, "whores, pimps, gamblers and sons of bitches," by which he meant Everybody. Had the man looked through another peephole he might have said, "Saints and angels and martyrs and holymen" and he would have meant the same thing.

Or consider the fictional village of Maconda in Gabriel Garcia Marquez's A Hundred Years of Solitude:

At that time Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.

Or open the pages of Jesmyn Ward's Sing, Unburied, Sing, Richard Russo's Nobody's Fool, or any story written by Alice Munro.

Place informs a character's worldview. During a recent webinar, Jesmyn Ward said that place should be evident in every simile, every metaphor, every sentence. “Where a character or narrator is from influences the way that character, thinks, speaks, or tells a story.”

Many stories are so connected to their place and setting that all we have to do is mention the title — James Joyce's Dubliners and Ulysses or Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury (set in the fabricated Yoknapatawpha County of the American South) — and we are instantly whisked to a specific time and place. It is inconceivable to think of these stories occurring in a different locale. “Every story would be another story, and unrecognizable as art,” Eudora Welty tells us, “if it took up its characters and plot and happened somewhere else.”

Place can tell us about a character's emotional state, aspirations or dreams. It can shape a character's life as well as our understanding of the story. Place in story can captivate and charm, thrill or frighten, repulse or infuriate us. It can even heal the heart. Here are four fine examples of place in literature:

Around the watchers, the city still made its everyday noises. Car horns. Garbage trucks. Ferry whistles. The thrum of the subway. The M22 pulled in against the sidewalk, braked, sighed down into a pothole. A flying chocolate wrapper touched against a fire hydrant. Bits of trash sparred in the darkest reaches of the alleyways. Sneakers found their sweetspots. The leather of briefcases rubbed against trouserlegs. A few umbrella tips clinked against the pavement. Revolving doors pushed quarters of conversation out into the street.

— Let the Great World Spin, Colum McCann

It is true that one is always aware of the lake in Fingerbone, or the deeps of the lake, the lightless, airless waters below. When the ground is plowed in the spring, cut and laid open, what exhales from the furrows but that same, sharp, watery smell. The wind is watery, and all the pumps and creeks and ditches smell of water unalloyed by any other element. At the foundation is the old lake, which is smothered and nameless and altogether black.

— Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson

The apartment we lived in was long and narrow, with windows in the front and in the back. The back caught the morning light and the front the slow, orange hours of the afternoon and evening. Even at this cool hour in late spring, it was a dusty, city light. It fell on paint-polished window seats and pink carpet roses. It stamped the looming plaster walls with shadowed crossbars, long rectangles; it fit itself through the bedroom door, crossed the living room, climbed the sturdy legs of the formidable dining-room chairs, and was laid out now on the dining-room table where the cloth — starched linen expertly decorated with my mother's meticulous cross-stitch — had been carefully folded back along the whole length so that Gabe could place his school blotter and his books on the smooth wood.

— Someone, Alice McDermott

At half past six on the twenty-first of June 1922, when Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov was escorted through the gates of the Kremlin onto Red Square, it was glorious and cool. Drawing his shoulders back without breaking stride, the Count inhaled the air like one fresh from a swim. The sky was the very blue that the cupolas of St. Basil's had been painted for. Their pinks, greens, and golds shimmered as if it were the sole purpose of a religion to cheer its Divinity. Even the Bolshevik girls conversing before the windows of the State Department Store seemed dressed to celebrate the last days of spring.

— A Gentleman in Moscow, Amor Towles

It is hard to think about story without place, and why should we? After all, place only enriches our reading experience and impacts us in ways we may never have imagined. So perhaps place isn't a “lesser angel” after all.

Eudora Welty says, “One place comprehended can make us understand other places better. Sense of place gives equilibrium; extended, it is sense of direction too. Carried off we might be in spirit, and should be, when we are reading or writing something good; but it is the sense of place going with us still that is the ball of golden thread to carry us there and back and in every sense of the word to bring us home.”

If you would like to reprint this article, please contact the author directly at bd****@ao*.com for permission.

- Should I Fictionalize My Memoir? - June 21, 2024

- Do I Need a Writing Coach? - July 13, 2023

- How to Improve and Inspire Your Writing: 7 Books That Will Pave the Way - April 25, 2022