You've written it—it's taken a long time and you've poured everything you have into it; you've shown it to people who Know About These Things and they say it's great, go for it, publish it yourself. Just get it “looked at” by someone, to “clean it up.”

So … who is that someone?

Is it a friend who reads a lot and has really good taste? Another writer? An English teacher? A successful blogger? People with these backgrounds may indeed have valuable feedback for you, which is important during other phases of your book's development, but they will not be equipped to prepare your book for the stages just prior to publication.

These days, with so many options for writers to self-publish and when even established publishing houses are suffering cutbacks in editorial staff, it's more important than ever to make sure you have the editorial backup to bring your book up to professional standards.

This means you'll need a copyeditor. And then a proofreader. Here's why.

As self-publishing guru Joel Friedlander says in 10 Things You Need to Know about Self-Publishing, “Nothing will sink your chances faster than publishing a book [or e-book] that's full or errors, typos, lack of continuity, factual mistakes, or other obvious signs that it needs work.” The last thing you want to convey to the public is that you're an amateur. Self-publishing doesn't mean your book does not merit being published, but being unprofessional about how that book is put together will signal to readers that there's a good reason you could not find a publisher. These books of yours are going to be around for a long, long time, and you'll want them to be ready for prime time.

What, Exactly, Is Copyediting?

Copyediting is the unsung art and craft that examines each line and each word for clarity and consistency, for spelling and grammar, for logic and credibility. A good copyeditor will look at both the larger and smaller picture, seeing that the chapters flow and the sequence makes sense, as well as trim and shape overwritten sentences that may obscure your point, watch for libelous statements, trawl captions, tables, lists, catch errors of fact, and note inconsistencies in logic, sense, and style.

What does all this mean? To give you an idea, here are a few decisions I needed to make and facts I needed to check for a book I'm currently copyediting:

Is it 33 or thirty-three? The 60's or ‘60s? A hundred dollars or $100? Red, white, and blue or red, white and blue? What about time— 2:00 a.m. or 2 a.m.? Or two in the morning? And is it a.m., am, AM, AM, or A.M.? AKA or a.k.a.? Makeup or make-up? T-shirt or tshirt? Theatre or theater? Warner Brothers or Warner Bros.? “Cheers” or Cheers? Hillary Swank or Hilary Swank? Blond or blonde? Even … copyeditor or copy editor?

And what about, say, subject-verb agreement, as in “A writer should always reread their work before showing it.” In this example, “their” refers to more than one writer, despite how conveniently nongender-specific the word their is in common speech. Solutions abound, but the lapse must first be noticed before it can be rectified and the sentence recast. (One way to go: “Writers should always read their work before showing it.”)

Some decisions, such as the treatment of numbers, are discretionary—style choices made according to the type of book. Others, like proper names or simple grammar, are nonnegotiable and if violated will brand your book as the work of a rookie, no matter how impressive or legitimate the content.

On a more refined level, a good copyeditor has a prodigious vocabulary to draw from and thus will try to find just the right word for the right intention—not the fanciest word, mind you, but the rightest. So your use of “clean” may end up edited to a more effective “tidy,” or your “very good” to a more compelling “accomplished.” Moreover, it's the copyeditor who will catch such inelegant or out-and-out incorrect usage as “reverie” when you mean “revelry,” or “compliment” when you intend “complement,” or “cache” when what you really want is “cachet.”

Along with the edited manuscript, your copyeditor will deliver a style sheet reflecting all decisions made, which the proofreader will use as a guide in the final-final read. (And yes, Virginia, you will also need a proofreader. Read on.)

Proofreading Too?

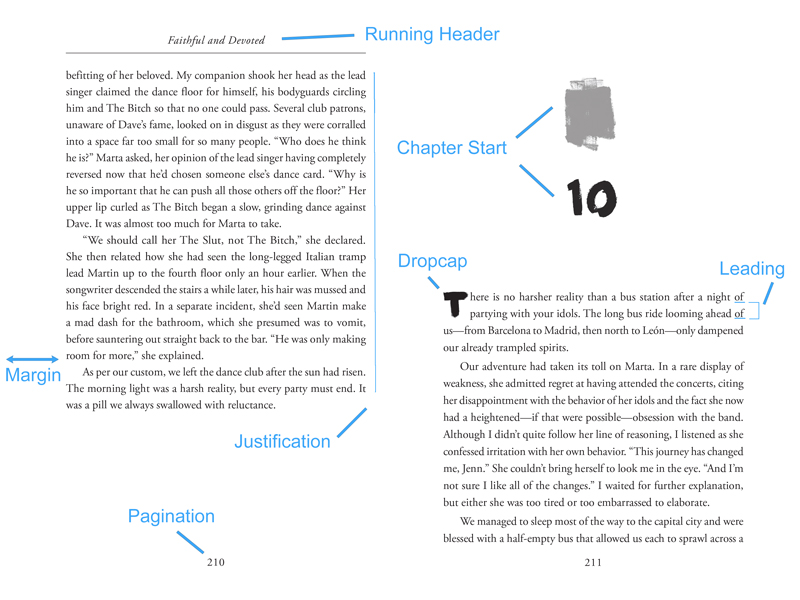

Not simply the last read, proofreading (also known as covering your hindquarters) is also the last line of defense before publication. A proofreader will examine the designed, laid-out version of your book, which will most likely be a PDF from the InDesign publishing program. (You‘ll definitely need to bring in a book interior designer if you want your published work to look like a real book and be competitive with others in its category.) That proofreader will not only catch typos and back up the copyeditor's decisions but will also scan for typographical issues— line breaks, widows, word breaks, headers and footers, page numbering, headings, font consistency, and oopses (to use the technical expression) of all kinds.

How Do I Find the Right Person to Do This?

Good news! You can start right here, on the LAEWG website, which lists our members, what genre we specialize in, and the kind of editing we typically do. These days, most of our work is done online and often from a distance, eliminating the need to zero in on someone in your immediate neighborhood.

Alternatively, you can consult any number of other editors' groups and associations, including the following:

Editorial Freelancers Association

If you know any authors who have hired an editor, by all means turn to them for input on their experience.

After getting the names of two or three copyeditors or proofreaders, email them with a brief description of your project and ask if they're interested, and if so when you might chat about the book, schedules, and fees.

Some editors may propose that you send them some sample pages to edit. I usually first assess whether the project is a good fit, and if it is, I suggest that I edit a sample chapter or do a few hours' work at my usual rate. If the result flies for the client, we're in business; if for some reason that's not the case, then the author has an excellent editorial start.

What to Ask When Interviewing an Editor

First up, of course, you'll want to know how much the work will cost, and the answer may be less than satisfying, because any editor in her right mind will first need to see the book—or a part of it—to assess the amount and type of work it will need. If you arrange with the editor for you to receive those sample edited pages I recommended previously, you'll see the kind of work she does as well as approximately how long it will take.

Most editors I know work at an hourly rate, though some may agree to negotiate a flat fee. Whatever the rate, a seasoned editor will cost more than a relatively inexperienced one—but then again, a seasoned editor will likely work faster and with greater acumen than someone with less experience. Here's where skill and maturity can work very much in your favor.

You might also ask about the editor's schedule and the anticipated turnaround. Your project may be coming at the end, in the middle, or even at the start of another project the editor has taken; depending on your own timetable, your place in the queue might have an impact on your partnership.

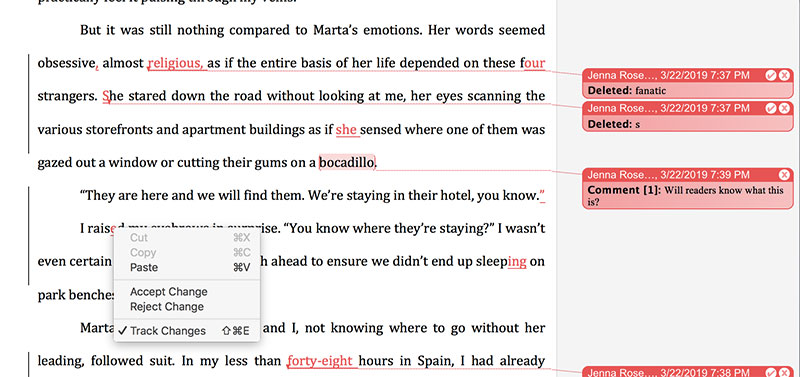

Ask how she works. Is it the old-school method of editing on hard copy? Or is it computer based, employing tools similar to Microsoft Word's Track Changes (available in all standard word-processing programs) to note all the changes but with the option of displaying them or viewing the manuscript as clean copy? The back-and-forth flow of work should be comfortable for you both and result in the most efficient process possible.

Will there be a contract, and what will it cover? The one I use essentially indemnifies me against any future lawsuits the author might incur but also allows for either party to discontinue the relationship as long as payments are up to date. It's a safety net I have never needed, but it is fairly standard. And be sure, as always, to read the fine print.

So go forth and publish—there's never been a better time to do it. Just give your book the best chance to be noticed in the best possible way.

![]()

WANT TO REPRINT THIS ARTICLE ON YOUR SITE OR IN YOUR EZINE? Go ahead, but only if you also include this: Copyright (C) 2014 Kate Zentall. All rights reserved. Contact: KZ******@gm***.com

- Why You Need an Interior Designer for Your Self-Published Book - June 7, 2022

- 6 Reasons Why You Should Write Your Book in Microsoft Word - December 8, 2020

- Tricks of the Editing Trade: Word, Track Changes, and the Master Document - May 16, 2019

3 Comments

Memoir: Do I capitalize proper names of birds, butterflies, and other animals?

Example: Yellow-rumped Warbler, Black Bear.

The names of birds and animals ad flora are typically not capitalized. Hence, black bear, yellow-rumored warbler, daisy. They are considered common nouns. Proper names tend to be unique, as in Sally, our pet yellow-rumped warbler, or Rex, the neighborhood black bear who rummages through our trash.

Thank you Kate for the info.